Dada and

photomontage

Dada is an armadillo. Everything is DADA. DADA is Instagram, hip-hip-hip and hollerbam, boom-boom-boom and ratatam, In, stram, gram. Login with Instagram and contribute to the worldwide digital DADA-Gram collage. Or explore the endless canvas, from top to bottom, left to right, bottom to left, like an infinite text written by a thousand hands. Intimate photos, extimate snapshots: mix your moments into the works of the magic DADAs.

Dada

1916

CUT, DADA, CUT!

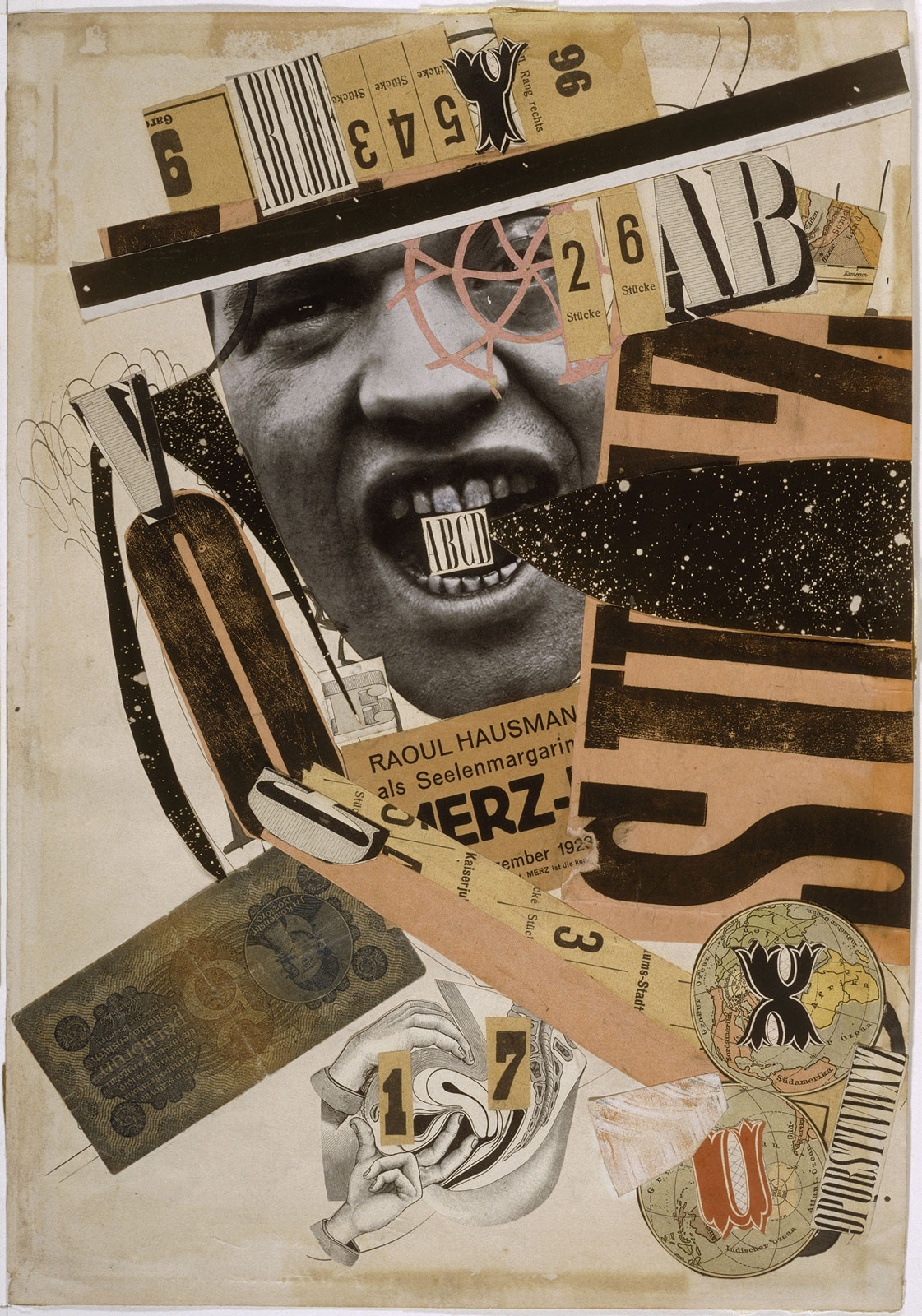

If DADA was a “total revolt against all habits, beliefs, and privileges” (in the words of Dadasoph Raoul Hausmann), then collage was the form of visual expression most congenial to it. Dada collages come into being and exist through contradiction. The spirit that inhabits them is one of productive destruction and illuminating disturbance.

Bourgeois notions of how art is made and what it should look like made the Dadas gag. And so they let their paint tubes go dry, because the painter-as-genius, flourishing his brush, and the painted work as a refuge of the imagination had done their time. They turned to the (only!) media of the day, newspapers and magazines, and with their scissors dissected the reproduced likeness of the present. The grotesquely shattered picture of the world in collage is de facto the likeness of a grotesque world, in which nationalism and militarism were carried forward despite the First World War. Dada collages hold up a distorting mirror to reality. In them, truth and its aberrations are twisted to the point of becoming recognizable. They are a kind of mental prosthetic for the viewer, made to break up calcified thinking and push aside repression. In this, Dada collage is a prototype for the socially critical art of the last hundred years. And as a cultural technique, collage – the joining together of originally disparate elements – has since become ubiquitous, from musical sampling through literary collages à la Herta Müller to body modification.

Dada

2016

Let’s be the parody of the world that selfies itself

The photomontage was DADA’s big constructive idea. And this big idea is the pillar of modern culture. Photomontage is a kind of hypertext before hypertext (defined in 1965 by its theorist, Ted Nelson, as a potentially infinite network of connections). Photomontage understands everything and grasps nothing of the times. It is mix and remix, sampling and new blood, stealth and chance, Snapchat and Instagram, at war and at large, mass media and the mass murder of ambient stupidity. From improvisation arises chaos, and from chaos, pleasure. The pleasure of laughter, not ridicule; the pleasure of shock and of the senses; the pleasure of “making something beautiful and forever joyful [using] elements from which one expected neither beauty nor joy.” (Hannah Höch)

Tristan Tzara, again: “With eyes shut, DADA places before action and above everything: Doubt. DADA doubts everything. Dada is an armadillo. Everything is Dada, too. Beware of DADA.”

Technology is taking giant steps today, as it did in 1916. A hundred years ago, it was photography, the print media, photojournalism, the first radios, the new assembly lines, mustard gas and muddy trenches, the dominance of the machine and the jubilation of a mechanical war, and DADA, which both appropriated and denounced a double culture that remains triumphant today: the culture of media and the machine. Kurt Schwitters cut up newspapers and advertising, Max Ernst snipped apart mail-order catalogs, and Hannah Höch sampled from women’s magazines.

A hundred years later, things have changed to the point of returning to the same point. DADA held up a funhouse mirror to the first generation of mass media. Let’s become the parody of the world that takes its own selfie.

Tristan Tzara, again and always: “The beginnings of Dada were not the beginnings of an art, but of a disgust.”